This long time-series data has enabled some interesting comparisons which suggest that the similar countries of New Zealand, Australia and Canada are making different policy choices in how they each deal with the issue of housing affordability. But before I get to that I take issue with the generalisations made in the introduction to the 2017 report made by Oliver Hartwich, Executive Director, of The New Zealand Initiative. He writes:

Germany is probably the country with the most boring housing market in the world. It is a place where nothing ever happens (at least as far as housing is concerned). German house prices remain stable, and if it had not been for the euro crisis and negative interest rates, the Germans would probably still be able to buy houses for the same prices in real terms that they paid twenty or thirty years ago.This is the first time I can remember someone suggesting that what is happening with housing affordability and housing supply in NZ and Australia can be usefully compared with what is happening in Germany and Switzerland. It's like comparing apples with oranges, as this table shows:

The story for other countries like Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and large parts of the United States is a different one. There, house prices have gone through the (now unaffordable) roof. My own housing research focused on this difference: Why did Germany (and similarly Switzerland) provide housing stability where much of the Anglosphere did not?

In a nutshell, the answer to this question has a lot to do with the way councils are funded. In jurisdictions where local decision-makers stand to gain from new development, they will be much more eager to make it happen. In Germany and Switzerland, council budgets largely depend on their ability to attract new residents and taxpayers. This is why both countries are have traditionally had a more responsive and flexible housing supply side. The available financial incentives to planners and councillors made all the difference to house prices in the long run. (Bold added).

The key figures in these two tables is the average annual population growth rates of major metro urban areas of Germany and Switzerland. I haven't gone back earlier in history, but it is generally accepted that the population increases in these countries is low, and given the age demographics show that death rates exceed birth rates, the forecast is for populations to slowly decline. There may be other policies adopted in these countries to change that long term trend. The point I'm making here is that population increases in the urban areas in these two countries has been between 0.3 and 0.4%/annum on average.

Compare this with Sydney, Auckland and Vancouver:

Population growth has been almost an order of magnitude greater. Growth and development patterns, and the related political economies, in the metro areas of Sydney, Auckland and Vancouver may be comparable. But they are very different from metro areas in Germany and Switzerland - too different to draw the kinds of conclusions that Mr Hartwich draws in his introduction to the Demographia housing affordability survey.

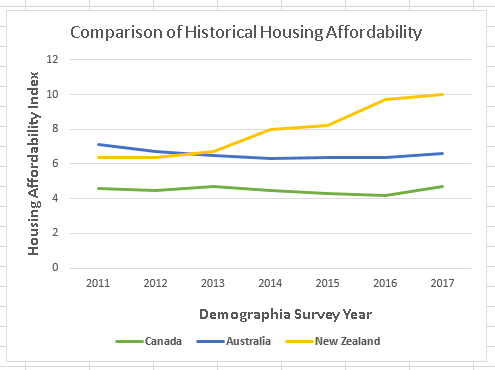

Interestingly, however, the time series Demographia findings for the metro areas that are comparable, suggest a rich area for further policy investigations, as this graph atests:

The data graphed here are from the Demographia Survey report tables ES-2 for the years 2011- 2017. To be fair, a variant of this graph is presented in the Demographia report but is not given the prominence it deserves. An explanation of the pattern observed - that Auckland's affordability index is spiralling away ahead of the indices for Australia and Canada.

This might be explained by Auckland's relatively higher population growth rate, combined with the fact that Australia and Canada are implementing more effective controls to manage demand.

One thing's for sure, because Auckland, Australia and Canada are all implementing smart growth land use policies to restrict sprawl. Yet there are other significant policy influences in effect. These need to be revealed and understood. Simply citing Germany and Switzerland as exemplars for a strategy where house prices are kept low by liberal land release policies does not cut the mustard.

No comments:

Post a Comment