Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Remembering My Grandfather

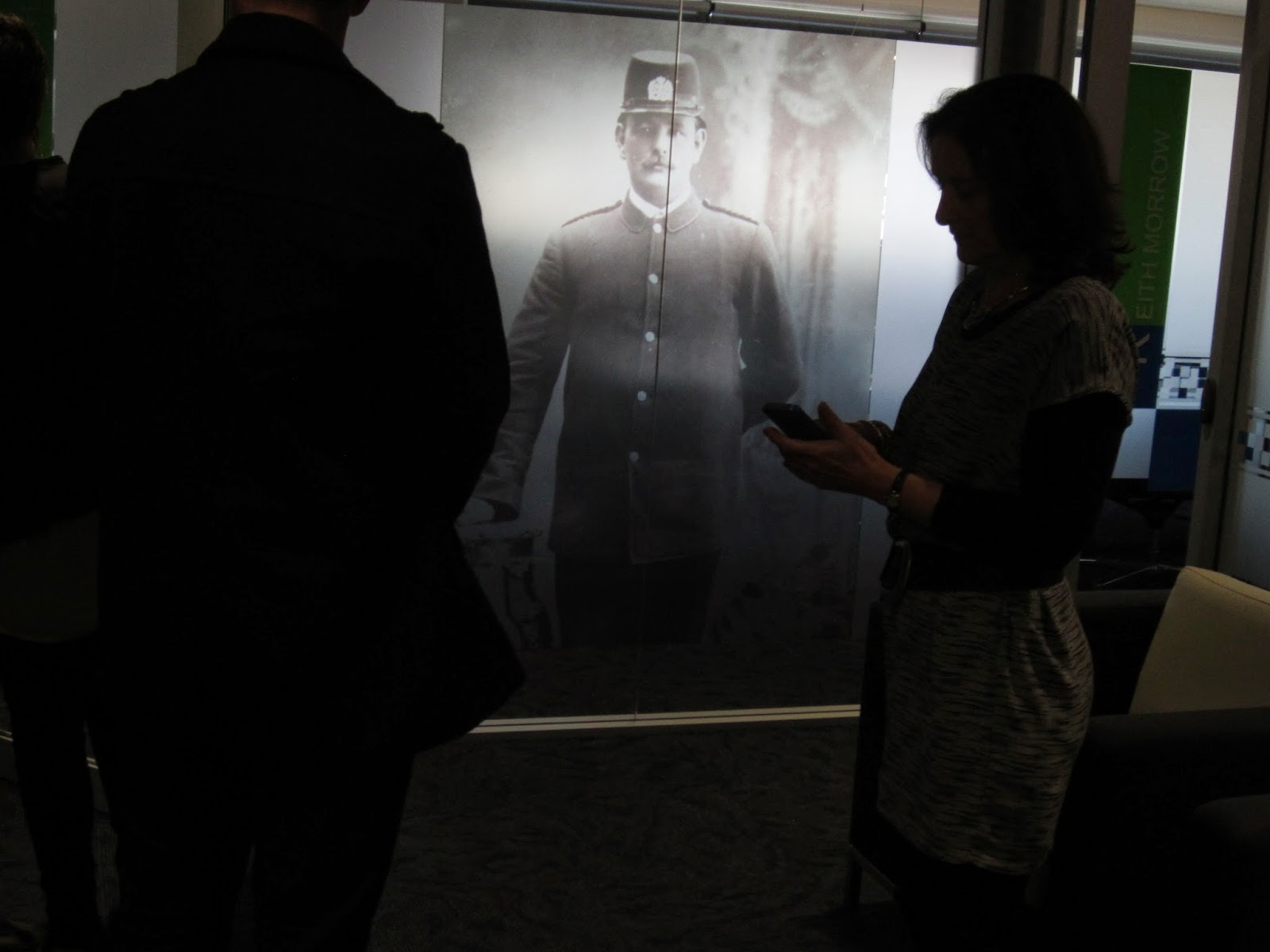

This bloke is my youngest brother, and the bloke looking over his shoulder is Constable Charles G. Smyth. He was our grand-father. And yesterday (22nd July) the new Boardroom at the NZ Police Trade Union offices (known as The NZ Police Association) was dedicated to him. We learned there that our grand-dad is the patron saint of the NZ Police Association.

Here's the boardroom. Family members standing around, and the Maori policeman giving the dedication and speech. (My daughter Emily, third from left, was among the great grandchildren and great-great grandchildren who also attended.)

On the wall is this picture and interpretation. I'm pasting here the Te Ara Encyclopedia entry on him here:

"Charles Gordon Smyth was born in Oamaru, New Zealand, on 17 April 1883, the son of Irish parents William Smyth, a baker, and his wife, Jane Macaffee. Charles excelled in school and at sports. He worked for some years in his father's baking firm, then in 1912 entered the New Zealand Police Force Training Depot in Wellington. He was appointed a constable on 11 July that year, and after initial stationing in Wellington was transferred to Dunedin on 8 January 1913.

In March 1913 Commissioner of Police John Cullen rejected police concerns over pay, discipline and conditions. City-based constables, particularly in Auckland, risked offending against police regulations banning 'combinations' and planned their own union. Government and police authorities, troubled by current industrial conflict in New Zealand, attempted to prevent what they saw as the virus of socialism gaining any influence in the police force.

Charlie Smyth, as he was known, arrived in Auckland on transfer on 31 March 1913. There he allegedly told a superior he had requested the transfer in order to help form a union. At the trades hall on 11 April several dozen policemen were helped by trade unionist Arthur Rosser to launch the New Zealand Police Association. Smyth was selected as the Auckland branch secretary. As such he was prominent in drawing up the rules and platform of the new organisation and in liaising with police in other parts of the country.

On 25 April Cullen assembled the Auckland police staff and assured them that they had nothing to fear from discussing their grievances. Smyth was the main spokesman for the police unionists and protested when an angry Cullen ended the meeting by inviting dissatisfied constables to resign. The minister in charge of police, A. L. Herdman, and the commissioner then moved to make an example of Smyth whom they regarded as an 'insolent' ringleader. Smyth's role in the association was said to have forfeited him the trust of the Auckland sergeants and officers. On 30 April he was ordered to transfer at once to isolated and rainy Greymouth where police were traditionally posted as a punishment. His comrades gave him a handsome presentation and rousing send-off.

In June 1913 Smyth was given four days' notice of dismissal, an obvious invitation to resign. He chose to 'expose' the 'police oligarchy' by forcing Cullen to sack him and then appealing the dismissal. He had allegedly been guilty of abandoning his post when guarding timber on the wharf and of making a false entry in the station book to disguise this. Similar misdemeanours were normally punished with fines or reprimands, and Smyth had both a clean record and evidence to support his contention that he had genuinely mistaken the time. Herdman blackened the constable's name in Parliament and denied his dismissal was connected with his union activity. The appeal was dismissed.

The newspaper New Zealand Truth stated that 'though the dogs of war were let loose on Smythe [ sic ], the last has not been heard of him'. Backed by members of Parliament, newspapers and unions Smyth campaigned to clear his name. However, by 1914 his efforts and the Police Association itself had effectively failed. The governing Reform Party was even claiming that Smyth had deliberately entered the Police Force to subvert it and 'secure its adhesion to the Federation of Labour'.

By then Smyth had returned to the baking industry in Oamaru. There, on 15 September 1914, he married Rose Mason, a weaver. In Morven, where he set up a bakery after the First World War, the couple were pillars of the local community. Smyth served on committees, played tennis and did charitable works. He died of cancer in Christchurch on 17 November 1927, aged 44. Rose Smyth, who was left with five daughters aged five to twelve, died the following year.

Charlie Smyth remained a well-known name in police union circles, and was honoured – accidentally, it appears – when his image appeared on a stamp officially issued for the New Zealand Police centenary in 1986. He was a man ahead of his time, regarded as the patron saint of the modern New Zealand Police Association which was founded in 1936."

This information is summarised in the boardroom dedication. It was interesting to learn that he had drawn up a model rule book for the new trade union, and that has become the basis of the rules today. Not only a gentleman - but maybe a scholar.

As we left, his image followed us to the lifts. An interesting family occasion. If you've got this far, you might be interested in this Truth Newspaper article which is a fantastic read.

And getting a little closer to the man, this exchange below is of letters from him, and criticising him, and even one from his father (my great grandfather) defending his dismissed son.

A personal explanation from Charles published in the Otago Daily Times, which also (scroll down) contains The Hon Herdman's, Minister of Justice, critical comments. This is a letter in the Oamaru Mail from Charles defending himself against the Minister's comments. Here is an example of a sub leader in the ODT attacking him, and an anonymous letter.

Here is Auckland Star's extracts of what he sent to would-be and current Police Association members.

And finally, a letter his dad wrote (scroll down - it's almost at the bottom of the column), in Charles Smyth's defence, in the Otago Daily Times.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Wednesday, July 23, 2014

Remembering My Grandfather

This bloke is my youngest brother, and the bloke looking over his shoulder is Constable Charles G. Smyth. He was our grand-father. And yesterday (22nd July) the new Boardroom at the NZ Police Trade Union offices (known as The NZ Police Association) was dedicated to him. We learned there that our grand-dad is the patron saint of the NZ Police Association.

Here's the boardroom. Family members standing around, and the Maori policeman giving the dedication and speech. (My daughter Emily, third from left, was among the great grandchildren and great-great grandchildren who also attended.)

On the wall is this picture and interpretation. I'm pasting here the Te Ara Encyclopedia entry on him here:

"Charles Gordon Smyth was born in Oamaru, New Zealand, on 17 April 1883, the son of Irish parents William Smyth, a baker, and his wife, Jane Macaffee. Charles excelled in school and at sports. He worked for some years in his father's baking firm, then in 1912 entered the New Zealand Police Force Training Depot in Wellington. He was appointed a constable on 11 July that year, and after initial stationing in Wellington was transferred to Dunedin on 8 January 1913.

In March 1913 Commissioner of Police John Cullen rejected police concerns over pay, discipline and conditions. City-based constables, particularly in Auckland, risked offending against police regulations banning 'combinations' and planned their own union. Government and police authorities, troubled by current industrial conflict in New Zealand, attempted to prevent what they saw as the virus of socialism gaining any influence in the police force.

Charlie Smyth, as he was known, arrived in Auckland on transfer on 31 March 1913. There he allegedly told a superior he had requested the transfer in order to help form a union. At the trades hall on 11 April several dozen policemen were helped by trade unionist Arthur Rosser to launch the New Zealand Police Association. Smyth was selected as the Auckland branch secretary. As such he was prominent in drawing up the rules and platform of the new organisation and in liaising with police in other parts of the country.

On 25 April Cullen assembled the Auckland police staff and assured them that they had nothing to fear from discussing their grievances. Smyth was the main spokesman for the police unionists and protested when an angry Cullen ended the meeting by inviting dissatisfied constables to resign. The minister in charge of police, A. L. Herdman, and the commissioner then moved to make an example of Smyth whom they regarded as an 'insolent' ringleader. Smyth's role in the association was said to have forfeited him the trust of the Auckland sergeants and officers. On 30 April he was ordered to transfer at once to isolated and rainy Greymouth where police were traditionally posted as a punishment. His comrades gave him a handsome presentation and rousing send-off.

In June 1913 Smyth was given four days' notice of dismissal, an obvious invitation to resign. He chose to 'expose' the 'police oligarchy' by forcing Cullen to sack him and then appealing the dismissal. He had allegedly been guilty of abandoning his post when guarding timber on the wharf and of making a false entry in the station book to disguise this. Similar misdemeanours were normally punished with fines or reprimands, and Smyth had both a clean record and evidence to support his contention that he had genuinely mistaken the time. Herdman blackened the constable's name in Parliament and denied his dismissal was connected with his union activity. The appeal was dismissed.

The newspaper New Zealand Truth stated that 'though the dogs of war were let loose on Smythe [ sic ], the last has not been heard of him'. Backed by members of Parliament, newspapers and unions Smyth campaigned to clear his name. However, by 1914 his efforts and the Police Association itself had effectively failed. The governing Reform Party was even claiming that Smyth had deliberately entered the Police Force to subvert it and 'secure its adhesion to the Federation of Labour'.

By then Smyth had returned to the baking industry in Oamaru. There, on 15 September 1914, he married Rose Mason, a weaver. In Morven, where he set up a bakery after the First World War, the couple were pillars of the local community. Smyth served on committees, played tennis and did charitable works. He died of cancer in Christchurch on 17 November 1927, aged 44. Rose Smyth, who was left with five daughters aged five to twelve, died the following year.

Charlie Smyth remained a well-known name in police union circles, and was honoured – accidentally, it appears – when his image appeared on a stamp officially issued for the New Zealand Police centenary in 1986. He was a man ahead of his time, regarded as the patron saint of the modern New Zealand Police Association which was founded in 1936."

This information is summarised in the boardroom dedication. It was interesting to learn that he had drawn up a model rule book for the new trade union, and that has become the basis of the rules today. Not only a gentleman - but maybe a scholar.

As we left, his image followed us to the lifts. An interesting family occasion. If you've got this far, you might be interested in this Truth Newspaper article which is a fantastic read.

And getting a little closer to the man, this exchange below is of letters from him, and criticising him, and even one from his father (my great grandfather) defending his dismissed son.

A personal explanation from Charles published in the Otago Daily Times, which also (scroll down) contains The Hon Herdman's, Minister of Justice, critical comments. This is a letter in the Oamaru Mail from Charles defending himself against the Minister's comments. Here is an example of a sub leader in the ODT attacking him, and an anonymous letter.

Here is Auckland Star's extracts of what he sent to would-be and current Police Association members.

And finally, a letter his dad wrote (scroll down - it's almost at the bottom of the column), in Charles Smyth's defence, in the Otago Daily Times.

1 comment:

- jafapete said...

-

You could mention the political context, perhaps? Your ancestor would be pleased, I think. After all, Massey's successors today have been very industrious in passing laws in recent years that have the effect of making it harder to organise trade unions, and which impact unfairly on unorganised workers. Tea breaks, for example, may soon disappear for the most vulnerable, un-unionised workers, as they did under the previous National Government.

-

July 24, 2014 at 12:54 PM

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

1 comment:

You could mention the political context, perhaps? Your ancestor would be pleased, I think. After all, Massey's successors today have been very industrious in passing laws in recent years that have the effect of making it harder to organise trade unions, and which impact unfairly on unorganised workers. Tea breaks, for example, may soon disappear for the most vulnerable, un-unionised workers, as they did under the previous National Government.

Post a Comment